Laios Konstantinos1, Lytsikas-Sarlis Pavlos1, Zografos Constantinos G.2, Noskova Irina3, Mourellou Evangelia 1, Tsoucalas Gregory1

History of Medicine and Medical Deontology Department, School of Medicine, University of 1Crete, Heraklion, Greece

2 School of Medicine, National and Kapodistrian University of Athens, Athens, Greece.

3Private nurse, Athens, Greece.

Correspondece Address: Konstantinos Laios, email: konstlaios@gmail.com.

doi:10.5281/zenodo.15710290.

Abstract

This historical vignette reports one of the first anatomical descriptions of the parotid duct and that of the plexus parotideus in 17th century. This discovery, the topographical description of plexus parotideus by Danish physician, anatomist theologian, Catholic bishop and geologist, Niels Steensen, in his work on the parotid duct, altered surgery of the parotid area. The term initially introduced was pes anserinus (goose-like foot), while later the English Latin term parotid plexus was established and is still used today. The term pes anserinus was included in the orthopedic medical nomenclature and was described in anatomy treatises as a cluster of nerves on the border of the parotid gland, raised by branches of the facial nerve (Latin: portio dura). The 17th century was the era during which the scientific field of anatomy began to clarify body’s topography, widely contributing to the evolution of surgery. Niels Steensen work provided significand aid to facial surgery and neuro-operations in the years to come.

Keywords: facial nerve, ductus stenonis, Gerard Leendertszoon Blasius, pes anserinus, history of neurology.

Introduction

The exact discovery of the plexus parotideus remains uncertain. Herophilus of Chalcedon (331-280 BC) and Erasistratus (ca 330-249 BC) were the first great anatomists of the Alexandrian School during the Hellenistic period, making significant contributions to the field of neurology. Allegedly, they conducted extensive examinations on more than 600 living slaves, in an attempt to unveil the secrets of human neurology. Unfortunately, their work has only been partly saved, and it is unclear whether they specifically described the plexus parotideus [1].

Galen was the next in line as a great physician of the Hellenic world. He documented nerves but failed to distinguish other entities [2]. During the Middle Ages, various speculative ideas about the function of nerves prevailed, yet systematic mapping of the nervous system only began after the authorization of dissections in Italy. During the Renaissance, anatomists and surgeons carefully documented the topography of the nervous system. Avicenna (980-1037), Albertus Magnus (ca 1200-1280), Master Nicolaus (ca. 1150-1200), Alessandro Benedetti (ca 1450-1512), Alessandro Achillini, (1463-1512), Leonardo Da Vinci (1452-1519), Jason Pratensis (1486-1558), Andreas Vesalius (1514-1564), Helkiah Crooke (1576-1648), William Harvey (1578-1657), Thomas Willis (1621-1675) and Jean Cruveilhier (1791-1874) were influential pioneers in advancing our understanding of the nervous system. However, it appears that Niels Steensen (1638-1686) was the first to conduct a detailed examination of the parotid area [3].

This historical vignette aims to document Steensen’s contributions to neurology and discuss the discovery of the plexus parotideus in the form of an informative documentary review.

Steensen life and work

Niels Steensen (1638 -1686, Latin name: Nicolaus Steno, Nicolaus Stenonius or Nicolas Stenon) [Figure 1], born in Copenhagen Denmark, had a turbulent early life. At the age of three, he was isolated for much of his childhood due to an unknown disease. Some years later, almost all the pupils of his school died from the plague. He survived and came under the patronage of Count Peder Griffenfeld, a statesman and royal confidant.

Figure 1. Nicolaus Steno, colorized engraving, 1868 after the portrait made by Christian August Lorentzen (1749-1828). |

At the age of 19, Steensen enrolled at the University of Copenhagen to pursue medical studies. Soon after, he travelled around Europe, visiting The Netherlands, France, Italy and Germany, to acquire knowledge in order to advance his career. In Amsterdam, Steensen began his anatomical studies under the renowned Dutch physician and anatomist, Gerard Leendertszoon Blasius (1627-1682). In 1666 he settled in Italy and was appointed professor of anatomy at the Medical School of the University of Padua. Though originally a Lutheran, Steensen later converted to Catholicism as a means to achieve his scientific objectives. Since he had a broader spectrum of interests, Steensen’s work included paleontology, geology, stratigraphy and crystallography [4].

Steensen’s religious beliefs did not diminish Steensen’s desire to uncover the construction of the human body. Fond of anatomical studies, he conducted numerous dissections on both human bodies and animals, often experimenting on the later [5]. His meticulous research led to the discovery of a previously undocumented structure, the duct of the parotid salivary gland. After identifying it in the crania of sheep, dogs and rabbits, he named it the “ductus Stenonis”. Blasius challenged Steensen’s claim to the discovery, indicating that he had identified the structure first, leading to a professional dispute. Despite the controversy, Steensen’s name prevailed, and the structure is now known universally as Stensen’s duct. Some later reports suggest that Steensen discovered the ductus stenosis when he was in Paris, while others place the discovery in Amsterdam in early 1660’s, when he had also identified the nerves of the area and published his treatise entitled “De Musculis et Glandulis Observatorium specimen, cum epistolis duabus anatomicis”, in 1664 [Figure 2] [5-8]. The plexus was described as a cluster of nerves located at the border of the parotid gland, formed by branches of the facial nerve (portio dura) and seen in the gland’s structure. This plexus was named pes anserinus due to its resemblance to the spreading foot of a goose. Tracing its branches in the opposite direction, reveals how they radiate over the side of the temples, face and upper part of the neck [9].

Figure 2. De Musculis et Glandulis Observatorium specimen, cum epistolis duabus anatomicis. Apud Jacobum Moukee, Lugduno-Batavum, 1664 by Nicolai Stenonis (Niels Steensen). |

The plexus

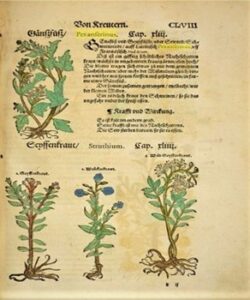

The term pes anserinus, meaning “goose foot” was included in Lexica of the 17th century [10-11] and was originally used to describe a species of plants [Figure 3] [12]. It was soon adopted to describe nerve plexuses in neuroanatomy [Figure 4] [13-14].

Figure 3. Pes anserinus plant, colored illustration, Eucharius Rößlin, 1569. |

From 1830 onward, the Latinized term plexus parotideus became more commonly used, and in some instances, it appeared in an English Latin combination as the carotid plexus [15]. From the late 18th century, the term was included in medical literature to refer specifically to the parotid plexus [9]. Encyclopedias of the time attributed the term pes anserinus to earlier generations of anatomists, yet they did not specify who originally introduced it [16]. Plates from the 17th century depict the pes anserinus. However, this depiction created by master anatomist-engravers of the era was often of such poor quality that it remains impossible to definitively attribute the discovery of the plexus to a specific scientist [17]. Modern anatomical terminology has adopted the term parotid plexus, while the term pes anserinus (pes: footlike; anserinus: goose) is now used to describe the superficial attachment site of three muscles: the sartorius, gracilis, and semitendinosus [18]. The fact that Steensen studied the topography of the parotid duct area without emphasizing on a separate description of the plexus parotideus, neither in his text, nor in a chapter title, may indicate that the plexus could have been already a known entity in anatomy by that time. The vague references to the plexus in encyclopedias as a matter of general knowledge contribute to the uncertainty surrounding the attribution of the discovery. Steensen was the first to publish a treatise on the anatomy of the parotid region and should be acknowledged at least for the delineation and complete description of the plexus in modern anatomy and surgery. He had adopted the conscientious methodology of Andreas Vesalius (1514-1564), gradually describing topographical anatomy only after conducting a thorough analysis of the area. Initially Steensen’s discovery was dismissed by his colleague Gerard Leendertszoon Blasius (1627-1682) as a result of a mistaken dissection. However, Steensen persisted in his research and, after dissecting a dog, ultimately provided definite evidence to support his discovery [5].

Figure 4. A page from Stephan Blancard’s Arzneiwissenschaftliches Wörterbuch in 1788, relating the term “pes anserinus” with neuroanatomy. |

Conclusion

Steensen is rather neglected as a master of facial or neurosurgery. However, he was a prolific anatomist with discoveries in the field of topographical human anatomy, giving one of the first complete descriptions of the parotid duct and the parotid plexus among other delineations in his work. His treatise “De Musculis et Glandulis Observatorium specimen, cum epistolis duabus anatomicis”, written in Latin is somehow unappreciated and his figure still awaits proper recognition.

References

- . Ghoneim L. Herophilus and Erasistratus: The Butchers of Alexandria. SCIplanet, 2017.

- Freemon FR. Galen’s ideas on neurological function. J Hist Neurosci. 1994;3(4):263-271.

- Finger S, Boller F, Tyler KL. History of Neurology. Elsevier, Amsterdam, 2009.

- Kermit H. Niels Stensen, 1638-1686: The Scientist who was Beatified. Gracewing Publishing, Gloucester, 2003.

- Strkalj G. Niels Stensen and the discovery of the parotid duct. Int J Morphol 2013;31(4):1491-1497.

- Kooijmans L. De anatomische lessen van Frederik Ruysch. Bert Bakker, Amsterdam, 2004.

- Steno N. De Musculis et Glandulis Observatorium specimen, cum epistolis duabus anatomicis. Apud Jacobum Moukee, Lugduno-Batavum, 1664.

- Philisen HP. Ductus parotideus Stenonianus. Tendlaegetidende 1960;64:221-248.

- Wilson E. Practical and surgical anatomy. Longman, Orme, Brown, Green, & Longmans, London, 1838.

- Withals J. A Dictionarie in English and Latine. Thomas Purfoot, London, 1916.

- Huloet R. Huloets Dictionarie, Newelye Corrected, Amended, Set in Order and Enlarged, with Many Names of Men, Townes, Beastes, Foules, Fishes, Trees, Shrubbes, Herbes, Fruites, Places, Instrumentes &c. And in Eche Place Fit Phrases, Gathered Out of the Best Latin Authors. In aedibus Thomae Marshii, Londini, 1572.

- Rößlin E. Kreuterbuch Künstliche Conterfeytunge der Bäume, Stauden, Hecken, Kreuter, Getreyde, Gewürtze. Mit eygentlicher Beschreibung derselbigen Namen, Vnderscheidt, Gestalt, Natürlicher Krafft vnd Wirckung. Item von fürnembsten Gethiern der Erden, Vögeln, vnd Fischen. Auch von Metallen, Gummi, vnd gestandenen Säfften. Sampt distillierens Künstlichem und kurtzem bericht. Bey Christian Egenolffs Erben, 1569.

- Blankaart S, Isenflamm JF, Ketten GE. Arzneiwissenschaftliches Wörterbuch worin nicht nur die zur Heilkunde gehörigen Kunstwörter, sondern auch die in der Zergliederungskunst, Wundarzneikunst, Apothekerkunst, Scheidekunst, Gewächskunde u. s. w. gebräuchlichen Ausdrüke deutlich, bestimt und kurz erklärt werden. Georg Philipp Wucherer, Wien, 1788.

- Halleri A. De partium corporis humani praecipuarum fabrica et functionibus, Opus quiquaginta annorum, Volume 8. Ex prelis Societatum Typographicarum, Bernae 7 Lausannae, 1778.

- Meckel JF. Manual of General, Descriptive, and Pathological Anatomy. Carey & Lea, Philadelphia, 1832.

- Chambers’s Encyclopaedia: Labrador-Numidia. W. and R. Chambers, London, 1864.

- Atkinsom J. Medical Bibliography. A and B. John Churchill, London, 1834.

- Panayiotou Charalambous C. The Knee Made Easy. Springer Nature, Cham, 2021.