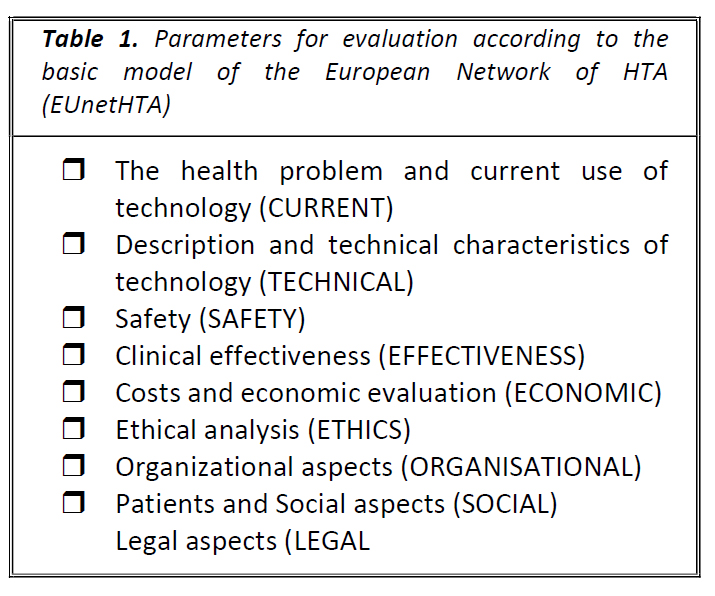

Review Article The Role of Epidemiology in Health Technology Assessment and Reimbursement of New Medicines: A Review Short title: Epidemiology and health technology assessment Aristea Kavvada,1 Nikos Syrigos,2 Adrianni Charpidou,3 Georgia Kourlaba,4 1National and Kapodistrian University of Athens, Greece 23rd Department of Medicine, National & Kapodistrian University of Athens, Greece 33rd Department of Medicine, National & Kapodistrian University of Athens, Greece 4 Faculty of Health Science, Nursing Department University of Peloponnese, Greece Corresponding Address: Georgia Kourlaba, PhD, Assistant Professor, Faculty of Health Science, Nursing Department University of Peloponnese, Chatzigianni Mexi 5, 115 28, Athens, Greece e-mail: kurlaba@gmail.com Abstract Objectives. After a medicinal product has been licensed, national health technology assessments (HTAs) are performed to ensure patients have affordable access to new treatments. However, little is known about the role of epidemiology in this phase. Therefore, the aim of this review is to summarize the impact of epidemiology on the HTA process, up until the final determination of the new drug reimbursement prices. Material and Methods. A literature review was conducted to identify the criteria, data sources, and reimbursement procedures used by various international and European HTA bodies. Results. Epidemiology is a vital component of both economic and clinical assessments of innovative drugs. It plays a crucial role in several stages of the HTA process, including: a) determining which health technologies will be assessed, b) providing information on the disease burden and unmet medical needs, and c) uncovering the economic worth of the product and projecting the financial effects of launching it in the market. d) ascertaining the conclusive confidential reimbursement amount by means of negotiation. The HTA process utilizes epidemiological data, obtained primarily from national representative databases containing real-world data, which is often hard to access, particularly in certain countries. Conclusion. Epidemiology serves as the foundation for the economic and clinical evaluation of cutting-edge medicines during the HTA phase. To guarantee the dependability of the evaluation, epidemiological information sourced from national representative databases should be employed. Keywords: epidemiology; reimbursement; health technology assessment; innovative drugs; real world data Introduction The etymology of 'Epidemiology' derives from the Greek words epi (upon), demos (the people), and logos (study of what befalls a population).1 The field investigates the frequency of disease occurrence in a population (descriptive epidemiology) and the underlying determinants (risk factors) impacting this frequency (analytical epidemiology).2,3 These determinants encompass natural, biological, social, cultural, and behavioral factors. Epidemiology is a fundamental science of public health that seeks to control health issues and prevent diseases.2,3 It provides comprehensive details about disease and health events, such as diagnosis, at-risk individuals, place and time of occurrence, causes, risk factors, transmission, consequences for the population, and the likelihood of risk escalation or mitigation.4 The importance of epidemiology in shaping health and public policy through evidence-based healthcare policymaking is becoming an increasing evident.5 At each stage of the healthcare policy-making process, epidemiology plays a significant role.6 In terms of assessing population health, epidemiology can aid in identifying the actual health requirements or dangers of a group, assessing the overall impact of health issues and their socioeconomic implications on society, and identifying disparities in health. Additionally, epidemiology can aid in assessing the effectiveness of interventions. When it comes to shaping healthcare policies and putting them into action, one can offer guidance in establishing objectives for preventing illnesses, simulate the effects of different interventions on the general health of the population, and furnish an impartial foundation for selecting which options are most worth pursuing, all of which are critical for effective implementation. Additionally, with respect to assessing the effectiveness of policies, it can aid in devising a systematized means of tracking health issues and identifying areas, where healthcare services may be deficient, allowing for better planning and the enhancement of present initiatives.6 In the pursuit of pharmaceutical and biological products, epidemiological investigation plays a crucial role. From the initial stages of research and development to authorization and post-marketing activities, epidemiology is an integral part of drug development, characterized by considerable expenses and time investment.7 The pharmaceutical industry employs epidemiologic research to identify medical needs that are not met and to gain insight into the burden of a targeted disease, which is manifested through mortality and morbidity rates, among other indicators. Companies also gather post-marketing safety data deemed necessary by regulatory authorities. In addition, epidemiological data is used by pharmaceutical firms to stimulate regulatory approval, particularly for rare conditions that are typically investigated through single-arm trials. In such cases, data from those trials are compared to information contained in existing databases (known as "historical controls") in order to derive a measure of the relative efficacy of the new product.8-10 Nevertheless, once a medicine has been licensed, national health technology assessments (HTAs) are conducted to ensure that patients have affordable access to the new drugs. Our aim in this narrative review is to present the role of epidemiology in the HTA and reimbursement of a new medicinal product, as no published work has explored this topic yet to our knowledge. Material and Methods To investigate the criteria, data sources, and reimbursement processes used by various international and European HTA bodies, a literature review was carried out. Relevant published material was scrutinized in both the PubMed database and Google Scholar using the keywords "health assessment technology AND epidemiology role AND/OR epidemiology effect AND/OR reimbursement procedures." A standardized data extraction form was used to extract data using these keywords, and the study followed the PRISMA-ScR (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for Scoping Reviews) guidelines. A total of 1272 results were initially found, but after carefully selecting and applying exclusion criteria, 36 references were ultimately included in the review. Results and discussion The HTA process serves as an important determinant for reimbursement decisions, aiding in the efficient allocation of healthcare resources. Its primary objective is to produce greater value for money spent by evaluating efficacy systematically and transparently, safety and economic data in a biased-free and strongmanner.11 Numerous European countries employ HTA procedures in approving innovative drug therapies.12-14 In accordance with the foundational model of the European Network of HTA (EUnetHTA), the process evaluates nine domains (Table 1) with the first four pertaining to clinical evaluation primarily based on global data like disease burden, allowing for a rapid assessment of new drug effectiveness.15 The remaining five focus more on non-clinical evaluation, assessing issues such as economic, social, ethical and legal aspects associated with national frameworks.15 Table 1. Parameters for evaluation according to the basic model of the European Network of HTA (EUnetHTA) Table 1. Relation between medical students and CVS

The role of epidemiology is vital in the entire process of HTA, beginning with horizon scanning and prioritization, extending to the support of unmet medical needs, clinical and economic evaluations, and the formation of managed entry agreements that ultimately determine the reimbursement price of innovative medicines. The prioritization and selection of health technologies to be assessed by HTA bodies are pivotal for public health. To ensure transparency, comprehension and practicality in the decision-making process, both theoretical and practical approaches have been published.8,16 These prioritize criteria including epidemiologic indicators, such as prevalence, incidence and disease-adjusted life expectancy to identify the disease burden and unmet medical needs for the prioritization of health technologies by HTA bodies, according to literature reviews.16-18 HTA bodies utilize various criteria to prioritize, including clinical outcomes, such as final or surrogate clinical endpoints and health- related quality of life outcomes, the presence or absence of alternative therapies, innovative value in terms of added therapeutic benefits, cost-effectiveness assessments along with budgetary impacts, and other forms of evidence, such as its placement in therapeutic protocols or potential benefits for specific sub- populations. Additionally, ethical considerations related to human dignity and necessity are also taken into account.8, 17 Two primary factors for prioritization in Sweden are the severity of the illness and the availability of treatment.17 More severe illnesses are given priority through Willingness to Pay (WTP). In Italy and Germany, "disease frequency" and "burden of disease" are explicitly or implicitly used for priority setting by HTA bodies.19 In Canada, the disease burden and current alternatives are key criteria for prioritizing HTAs. 16 The evaluation of a new health technology by HTA entities heavily relies on the concept of Unmet Medical Need (UMN). Recent research has classified UMN definitions into three categories: (a) those solely influenced by the availability of other treatments, (b) those considering the disease's severity or burden in addition to alternative treatments, and (c) those encompassing three aspects – alternative treatment availability, disease severity/burden, and patient population size.8 The size of patients’ population depends directly on the prevalence and the incidence of the disease and usually larger population means larger UMN. However, even for small populations, an UMN might exist, especially when treatment alternatives are completely lacking and the disease is life threatening (i.e., orphan medicines).8 The impact of living with illness, disability, and premature death is measured by the burden of disease (BoD), which is a component of UMN.20 BoD is quantified by the disability-adjusted life years (DALY), which reflects the difference between a life lived in perfect health and the current health status. This is measured by the number of healthy life years lost due to illness (Years Lived with Disability, YLDs) and premature death (Years of Life Lost, YLLs).20-22 In essence, BoD combines mortality and morbidity into a single, comprehensive metric. 22 To determine YLLs, the number of deaths from a particular disease or injury in a reference year is multiplied by the remaining life expectancy at the age of death within each age and sex group. YLDs, on the other hand, are calculated by multiplying the prevalence or incidence of a disease by the severity of disability associated with it, the duration of the disease, and its severity distribution.20 This requires extensive epidemiological modeling and may draw on various data sources, such as patient-reported outcomes, expert opinions, and literature research. Accurate mortality data is essential for YLL estimation, whereas YLD estimation is a more complex process.20 It has been demonstrated from the aforementioned points that epidemiology plays a significant part in bolstering the UMN's belief that a novel medicinal product will be sufficient. Upon examination of the assessment standards employed by European HTA organizations, we have come to comprehend that the concept of burden of disease is evaluated in either an implicit or explicit manner, with unmet medical needs being one of the interpretations alongside severity and prevalence (i.e., rarity) of the disease. Formal criteria for determining medical need vary across countries. In France, the presence of alternative therapies and disease severity are defining factors. In Germany, disease severity is included in the clinical benefit assessment. In England, unmet clinical need and availability of alternative therapies are important factors, with disease severity particularly relevant for life-extending medications for patients with limited life expectancy.17 In Italy, the Netherlands, Spain, and Poland, the evaluation process generally considers the severity and prevalence of the disease, as well as the availability of treatments, whether explicitly or not.17 In Greece, the clinical benefit is a major evaluation criterion and its determination considers the severity and burden of the disease.23 In Australia, epidemiology holds significant weight in the evaluation process and, within the context of social values, makes allowances for rare cases, where patients have no other treatment options, and their condition is expected to lead to premature death.18 Epidemiology plays an important role in supporting the economic value of a product across various economic domains. Assessment of cost-effectiveness outcomes. During the HTA process, a new drug undergoes assessment of its economic value through data analysis of cost- effectiveness. This involves a comparison of two or more interventions in terms of monetary cost (€) and physical effectiveness (e.g., life years gained, reduction of blood pressure in mmHg). The resulting Incremental Cost Effectiveness Ratio (ICER) reflects the additional cost required for a patient treated with the new drug to achieve an additional level of effectiveness compared to the standard of care or an alternative therapy. This ratio is based on the calculation of the cost per unit of effectiveness gained (e.g., life year, quality adjusted life year, event avoided).24-26 In order to establish the cost- effectiveness of a new treatment, it must be determined that the calculated ICER falls below a predetermined threshold, known as the willingness to pay (WTP) threshold. The World Health Organization (WHO) recommends a WTP threshold of 1 to 3 times the gross domestic product (GDP) per capita of the relevant country.25,27 However, there is evidence based literature demonstrating that this WTP threshold is extremely higher for orphan drugs and end of life treatments.28 A mounting collection of literature suggests that the WTP threshold for orphan drugs and end of life treatments is notably high. Berdud et al, research, for instance, indicates that the proposed incremental cost- effectiveness threshold (CET) for orphan drugs is reasonably adjusted to £39.1K per QALY at the orphan population cut-off. Additionally, for ultra-orphan drugs, the adjusted CET is estimated to be even higher at £937.1K.29 The three criteria used to classify a drug as an orphan and assess its cost-effectiveness at a higher WTP threshold include: (a) Treating patients with short life expectancy, usually under 24 months, (b) Providing evidence that the new treatment offers a prolongation of life of at least three months compared to the current NHS standard, and (c) Being licensed for a small patient population. These criteria highlight the significance of epidemiological evidence in evaluating the cost- effectiveness of medicinal products, as it is utilized to classify drugs as orphan and trigger higher WTP thresholds. NICE (National Institute for Health & Care Excellence) recognizes that the rarity of the disease plays a key role in the evaluation of orphan drugs, and it has been decided that there is an intention to pay more for rare and serious diseases.17 Budget Impact Analysis. Apart from cost-effectiveness analysis, budget impact analysis is usually assessed by the HTA bodies to determine the impact that the reimbursement of the new product might have on the budget of the payer for a pre-defined time horizon.31 The framework facilitates a comparison of two scenarios. The first pertains to the current state of the market, while the second envisions the future market situation after the introduction of a new treatment. This comparison captures the percentages of newly diagnosed and existing eligible patients that the new treatment is expected to attract from the existing options. The budget impact analysis measures the ramifications of this adoption on the healthcare system. It appraises its impact on a specific target population using various epidemiological indicators, such as mortality, disease prevalence, percentage of diagnosed and treated patients, and possible side effects. Furthermore, it takes into account the data on resources used and the unit costs of any other related healthcare services. Ultimately, the total cost of each scenario is evaluated and compared to determine the fiscal implications of adopting the new treatment.32 Budget impact analysis relies heavily on epidemiology as it provides essential indicators such as prevalence, incidence, and mortality rates which help to determine the number of eligible patients for new treatments. Other important factors include the expected number of patients to be treated and the average survival time after diagnosis, also play a critical role. To accurately estimate the eligible population over the next 5 years, projections for epidemiological indicators must be used. These projections are based on historical data and assist in determining the patterns of these indicators. The value of epidemiology in negotiation and reimbursement. Negotiation is the final stage of the process before the final decision for reimbursement or not of the new medicinal product. The main task of the Negotiation Committee is to negotiate prices of medicines that have received a positive recommendation by the HTA Committee and inform back the HTA Committee about the agreement concluded with manufacturers (if any). The agreements are divided into financial and outcome-based agreements. Financial based agreements are related to the total cost of the new treatment either per patient or for the entire target population and the outcome-based agreements relates to the effectiveness of new treatment in daily clinical practice.33 Epidemiology plays a dominant role in the negotiation process. The appropriate population size for the approved indication of a new drug can influence the negotiation strategy. This means different price for different population groups. The bigger the target group, the bigger discounts the drug companies ask for, and vice versa. This applies both to price-volume contracts, which are the most used financial-based contracts, and to contracts with a ceiling on medical costs (closed budgets). Therefore, knowledge of the epidemiological indicators of the disease, such as incidence, prevalence and mortality, contributes greatly to the correct calculation of the target population. Thus, given the treatment plan and recommended daily dose for the appropriate patient, the expected number of units to be sold can be estimated. This is considered as an important parameter because the deal price depends on this expected amount.34 In performance-based contracts, particularly conditional maintenance contracts and performance-based contracts, reimbursement applies only to those patients who respond to treatment or subsets of patients. This response is measured by epidemiological indicators per patient, such as impact on mortality and survival, impact on morbidity (symptoms or worsening), safety data and, achievement of therapeutic milestones over time periods.34 Sources of epidemiological data for pricing and reimbursement. Epidemiological evidence certainly plays a key role in the reimbursement process. Ideally, the data needed to assess disease epidemiology should be collected from nationally representative systems with factual data that are sure to be reliable sources. Instead, incidence estimates are usually derived from multiple real-world data sources based on what is currently available to describe the epidemiology of the disease. Real-world data is categorized into data extracted from primary sources and data extracted from secondary sources. Primary sources are classified as prospective and retrospective studies that are designed and implemented to fulfill a predefined research objective. Secondary sources include characterized databases with patient-level data developed for other purposes (e.g., medical records, electronic medical records, benefit data, laboratory/biomarker data).35-36 Another source of real-world data might be face-to-face interviews with key opinion leaders or advisory boards. It goes without saying, that the last is the less robust method for extraction of epidemiologic estimates, but still is an option in absence of any data from other sources. In case that a specific epidemiologic indicator is available from more than one sources, with none of these being a nationally representative database, a systematic review and meta-analysis should be conducted to obtain a pooled figure after considering the quality of each available study. Finally, only high- quality studies should be taken into account to obtain a robust pooled estimation for the epidemiological data. It is widely accepted that epidemiology is the cornerstone of the new drug development and reimbursement process, and epidemiologic data are usually obtained from real data sources. However, there are difficulties in obtaining reliable epidemiological data. First, although it is generally accepted that data collected from national health databases would be more representative and reliable, such databases are almost non-existent in most countries. Second, even when such databases are available (i.e., electronic prescribing systems, patient registries, etc.), access is limited. Third, even when national health databases exist, they are characterized by poor quality due to the lack of a standardized methodology for actual data entry and analysis.34 There is an urgent need to develop disease- specific registries in each country. The development and appropriate use of treatment protocols by healthcare professionals could also help to reflect daily clinical practice and produce high-quality real-world data. Real- time visibility and access to all stakeholders (i.e., MAHs, regulators, public health decision makers, patient organizations) is another important tool for improvement.35 Digitization could definitely help develop efficient, high capacity and fast database systems. The quality, quantity and validity of RWE are of the greatest importance, because they can contribute to the development of constructive and transparent discussions that lead to transparent and comprehensive decisions about the rational allocation of medical resources not only for curative therapy, but also for prevention. Conclusions Epidemiology plays a central role in health technology assessment and the substitution of new drugs. It is used internationally in the stages of the evaluation and reimbursement process for new medicines, from the priority of the products to be evaluated to the final confidential price of those products. Access to National Health Service databases is necessary to obtain representative and reliable epidemiological data to facilitate the HTA process. Their development and use require excellent planning, dedicated well-trained staff and budget, and good cooperation between all stakeholders. References 1. Principles of Epidemiology in Public Health Practice, Third Edition. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. An Introduction to Applied Epidemiology and Biostatistics. May 18, 2012. Accessed June 2, 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/csels/dsepd/ss1978/lesson1/secti on1.html 2. Trichopoulos D, Lagiou P. General and Clinical Epidemiology. 2nd ed. Scientific Publications Parisianou; 2011. 3. Lagiou P, Lagiou A, Kalapothaki V, Adami H.O., Trichopoulos D. Epidemiologic investigation of the etiology of chronic diseases: Review. Archives of Hellenic Medicine 2005;22(1):36-49 https://www.mednet.gr/archives/2005-1/pdf/36.pdf 4. Muir Gray JA. Evidence-based Healthcare: How to make health policy and management decisions. 1st ed. Churchill Livingstone; 1997. 5. Spasoff A.R. Epidemiology Methods for Health Policy. 1st ed. Oxford University Press; 1999 6. Dussault G. Epidemiology and Health Services Management. Epidemiological Bulletin. 1995;16(2) 7. Haas J. Commentary: Epidemiology and the pharmaceutical industry: an inside perspective. International Journal of Epidemiology 2008;37:53-55. doi:10.1093/ije/dym264. 8. Vreman R.A, Heikkinen I, Schuurman A, et al., Unmet Medical Need: An Introduction to Definitions and Stakeholder Perceptions Value Health. 2019;22(11):1275–1282 doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2019.07.007. 9. Rudrapatna V.A., Butte A.J. Opportunities and challenges in using real-world data for health care. J Clin Invest. 2020;130(2):565–574. https://doi.org/10.1172/JCI129197. 10. Dal Pan G.J., Raine J, Uzu S. The Role of Pharmacoepidemiology in Regulatory Agencies Pharmacoepidemiology, 6th Ed. John Wiley & Sons Ltd; 2020 11. Principles of Epidemiology in Public Health Practice, Third Edition. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. An Introduction to Applied Epidemiology and Biostatistics. May 18, 2012. Accessed September 4, 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/csels/dsepd/ss1978/lesson1/secti on2.html 12. Sullivan P.W., Li Q, Bilir P., et al., Cost- effectiveness of omalizumab for the treatment of moderate-to-severe uncontrolled allergic asthma in the United States, Curr Med Res Opin. 2020;(36):1, 23-32, doi: 10.1080/03007995.2019.1660539 13. Kanters, T.A., Hoogenboom-Plug, I., Rutten- Van Mölken, M.P. et al. Cost-effectiveness of enzyme replacement therapy with alglucosidase alfa in classic- infantile patients with Pompe disease. Orphanet J Rare Dis 2014;9(75). https://doi.org/10.1186/1750-1172-9-75 14. Van Den Brink R., “Reimbursement of orphan drugs: the Pompe and Fabry case in the Netherlands.” Orphanet J of Rare Dis 2014;9(1) https://doi.org/10.1186/1750-1172-9-S1-O17 15. EUnetHTA Joint Action on HTA 2012-2015 HTA Core Model Version 3.0. 25 Jan 2016. Accessed June 4, 2021. https://eunethta.eu/wpcontent/uploads/2018/03/HTAC oreModel3.0-1.pdf 16. Husereau D., Boucher M, Noorani H., Priority setting for health technology assessment at CADTH International J of Technol Assess Health Care 2010;26(3): 341–347. doi: 10.1017/S0266462310000383. 17. Angelis A, Lange A, Kanavos P, Health Quality Ontario, Health Technology Assessments: Methods and Process Guide, version 2.0, March 2018 –Using health technology assessment to assess the value of new medicines: results of a systematic review and expert consultation across eight European countries Eur J Health Econ 2018;19:123–152. doi:10.1007/s10198-017- 0871-0 18. Whitty J.A., Littlejohns P., Social values and health priority setting in Australia: An analysis applied to the context of health technology assessment. Health Policy 2014;2 doi:10.1016/j.healthpol.2014.09.003 19. Specchia M. L. et al. Epidemiol Prev 2015;39(4) Suppl 1: 1-158 20. Murray CJL, Lopez AD, Harvard School of Public Health (Cambridge, Mass.), WHO, IBRD. The Global Burden of Disease: A comprehensive assessment of mortality and disability from diseases, injuries, and risk factors in 1990 and projected to 2020. Published by Harvard School of Public Health on behalf of the World Health Organization and the World Bank. 1996. 21. Lopez AD, Mathers CD, Ezzati M, Jamison DT, Murray CJ. Global burden of disease and risk factors. A copublication of Oxford University Press and The World Bank: Oxford University Press. 2006. 22. Devleesschauwer, B., Maertens de Noordhout, C., Smit, G.S.A. et al. Quantifying burden of disease to support public health policy in Belgium: opportunities and constraints. BMC Public Health 2014;14:1196. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-14-1196 23. Government Gazette FEK 2768/Β/11.07.2018 24. What is the incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER)? GaBI Online. December 03, 2010 Accessed June 15, 2021 https://www.gabionline.net/generics/general/What-is- the-incremental-cost-effectiveness-ratio-ICER 25. Woods B, Revill P, Sculpher M, Claxton K, Country-Level Cost - Effectiveness Thresholds:Initial Estimates and the Need for Further Research, Value in Health 2016;19(8):929-935. doi:10.1016/j.jval.2016.02.017 26. Tammy OT, Cost - Effectiveness versus Cost– Utility Analysis of Interventions for Cancer: Does Adjusting for Health-Related Quality of Life Really Matter? Value in Health 2004;7(1):70-78. doi:10.1111/j.1524-4733.2004.71246.x 27. Sullivan P.W, Li Q, Bilir P et al., Cost- effectiveness of omalizumab for the treatment of moderate-to-severe uncontrolled allergic asthma in the United States, Curr Med Res Opin, 2020;36(1): 23-32. doi: 10.1080/03007995.2019.1660539 28. Mauskopf JA, Sullivan DS, Annemans L et al, Principles of good practice for budget impact analysis: report of the ISPOR Task Force on good research practices — budget impact analysis. Value Health 2007;10(5): 336- 47. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4733.2007.00187.x. 29. Berdud M, Drummond M, Towse A. Establishing a reasonable price for an orphan drug. Cost Eff Resour Alloc 2020;18:31 doi:10.1186/s12962-020-00223-x 30. Appraising life-extending, end of life treatments. National institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. July, 2009. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/gid- tag387/documents/appraising-life-extending-end-of-life-treatments-paper2 31. Gonçalves F.R., Santos A, Silva C, Sousa G. Risk-sharing agreements, present and future Ecancer medicine science 2018;12:823. doi:10.3332/ecancer.2018.823 32. Leelahavarong P. Budget Impact Analysis, J Med Assoc Thai 2014; 97 (Suppl. 5): S65- S71 33. Ferrario A, Kanavos P. Managed Entry Agreements for Pharmaceuticals: The European Experience. EMiNet, Brussels, Belgium. June 2013. http://eprints.lse.ac.uk/50513/ 34. Campbell D. Indication-specific pricing, what should manufacturers expect in key markets HTA- Quarterly. Winter 2017 accessed: January 19, 2017 35. De Lusignan S, Crawford L, Munro N. Creating and using real-world evidence to answer questions about clinical effectiveness. J Innov Health Inform. 2015;22(3):368-373. doi: 10.14236/jhi.v22i3.177. 36. Jarow JP, LaVange L, Woodcock J. Multidimensional Evidence Generation and FDA Regulatory Decision Making: Defining and Using “Real-World “Data. JAMA. 2017;318(8):703 doi:10.1001/jama.2017.9991

visibility_offDisable flashes

titleMark headings

settingsBackground Color

zoom_outZoom out

zoom_inZoom in

remove_circle_outlineDecrease font

add_circle_outlineIncrease font

spellcheckReadable font

brightness_highBright contrast

brightness_lowDark contrast

format_underlinedUnderline links

font_downloadMark links