Tsoucalas Gregory

Department of History of Medicine and Medical Deontology, School of Medicine, University of Crete, Heraklion, Greece

Correspondece Address. Gregory Tsoucalas, Department of History of Medicine and Medical Deontology, School of Medicine, University of Crete, Voutes, 71003 PC, Heraklion, Grete, Greece. Email: gregorytsoukalas@uoc.gr

Τheophanes Nonnus (or Nonnos, Greek: Θεοφάνης ο Νόννος), lived during the reign of Emperor Constantine VII the Porphyrogenitus. (Fig.1)

Figure 1. Miniature depiction of Constantine VII from the Byzantine Codex of the 15th century “Cronaca di Zonara e altri brevi testi di storia bizantina”. |

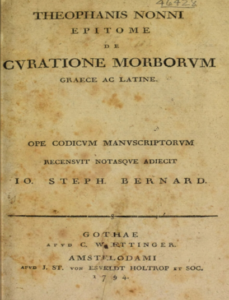

Because of his great education and skills became emperor’s chief physician. Theophanes diligently collected what Orivasius, Aetius of Amida, Paulus of Aegina and Alexander Trallianus had written in their treatises, being a majestic compiler (Greek: ερανιστής). This concept to compose an encyclopedia of medical knowledge after an order given by the emperor was a common practice during the Byzantine Empire [1-2]. Theophanes wrote a work of great interest on the History of medical terminology entitled “Synopsis in an Epitome of the Medical art” (Figure 2), containing two hundred and ninety-seven chapters. Other know works attributed to him are “Eye Diseases”, “Dietary” and a pharmaceutical collection of seven hundred and twenty-five chapters, named “Euporista” (Substances for best way to live), which may be found in the Paris National library [3-6]. Among others he gave instructions for the best eruption of new teeth, childhood epilepsy, prevention of infectious diseases and environmental contamination, tetanus, conjunctivitis, eye and uterine cancer, the treatment of heart shock and heart rhythm disorders, tonsillitis, bronchial asthma, lienteria, drugs for gallstones, terror, migraine, coma, and the suicidal tendency of psychiatric patients. Theophanes was the first to apply an “abdominal puncture on ascites”, a term he was the first to use [5, 7]. One of his mistakes in anatomy was that the “the larynx is the mouth (upper opening) of the tracheal artery”. Meanwhile, he knew how to perform direct laryngoscopy [5, 8]. Theophanes second name “Nonnus” is under dispute, as many researchers based on a testimony of the Vienna Codex, attribute to him the name “Chrisovalantes”, noting that this may have been derived from the Chrysovalantou Monastery or from the term “chrisovalanon” meaning “golden repository”, a great epithet for a majestic physician. A family named “Chrysovalantitai” existed in the archives of the Byzantine Empire and there is a possibility that Theophanes was one of its members. Some researchers also believe that the order considered to have been given by Constanrtine the VII is rather a dubious belief, as Theophanes’ work was much shorter than Oribasius’ and there is the possibility that the emperor just adopted Theophanes work to promote his name, or just gave Theophanes name in a secondary value treatise, as Theophanes was his personal friend and desired to help his social elevation. Whatever the case may be, Theophannes Nonnus’ work stands as a significant echo of the 10th century Byzantine Medicine [9].

Figure 2. Theophanis Nonni Epitome de Curatione Morborum. Gothae, 1794. |

The period of the Macedonian dynasty and the Emperor’s Constantine VII the Porphyrogenitus was one of the most glorious and celebrated periods of the Byzantine Empire. Both science and art developed widely and their fruits resulted for the era to be characterized as the “Macedonian Renaissance”. Theophanes was one of the most eminent physicians of the era in Constantinople, belonging to the inner cycle of the Emperor. His writings included references in pathology, gynecology, neurology and pharmacology [10-11]. His practice was based in the ancient Greek and Greco-Roman medicine, introducing however his own medical views, emphasizing for example in antiseptics [12]. Although Theophanes grew up into one of the most significant medical figure of the Byzantine era, little is known for his life. This fact is testified in various Lexica, where only his name and profession is mentioned [13-14]. His figure was so important that had been included in Lexica of Ancient Greek Philology, probably due to the concept of the ancient Hellenic literature (Greek: αρχαία Ελληνική Γραμματεία), including all treatises in a unified base [15].

The mystic which surrounds Theophanes’s life provokes researchers to connect fragments of his work and to unveil aspects from future findings.

References

- Pournaropoulos GK. Teaching Medicine in Greece. Asclepius 1930;(4)10: 1080.

- Eutichiades A. Introduction to Byzantine Therapeutics. Parisianos, Athens, 1983: 291.

- Emmanouil Emm. History of Pharmaceutics. Athens: Pyrsos, 1948.

- Charames J. The evolution of surgery in ophthalmology. Medical Chronicles 1933;6: 13-21.

- Nonni Medici Clarissimi, De Omnium Particularium Morborum Curatio [The Epitome of Theophane Nonnus]. Iosias Rihelius, Strasbourg, 1568: 166-167.

- Nonnus. Dionysiaka, Book 35, Line 61-62. Lipsiae: Fridericus Graefe, 1819.

- Theophanes (Noni). Synopsis Artis medicae ex Oribasio potissimum collecta,. Graece. Brit. Mus. Add. 17,900, London.

- Demetriades D. The evolution of Otorhinolaryngology. Archives of Medicine and Biology 1918;12: 72.

- Sonderkamp JAM. Theophanes Nonnus: Medicine in the Circle of Constantine Porphyrogenitus. Dumbarton Oaks Papers, Symposium on Byzantine Medicine 1984;38: 29-41.

- Balogiannis S. Neuroscience in Byzantium. Egkefalos 2012;49: 34-46.

- Browning R. The Byzantine Empire. Weidenfeld and Nicolson, London, 1980.

- Ramoutsaki IA, Dimitriou H, Markaki EA, Kalmanti M. Management of childhood diseases during the Byzantine period: III, Respiratory diseases of childhood. Pediatrics International 2002;44: 460-462.

- Prioreschi P. A History of Medicine: Byzantine and Islamic medicine. Horatius Press, Omaha, 1996.

- Magnes DD. Lexicon Historico-Mythical. Hellenic Typography of Fransisco Andreola, Venice, 1834.

- Donalson JW. History of ancient Greek literature from the founding of the Socratic Schools to the fall of Constantinople by the Turks. Williams and Norgate, London, 1871